Among the many New York casualties of Covid-19 was a plan for a citywide Asia Society Triennial set to open in June 2020. As envisioned by co-curators Michelle Yun and Boon Hui Tan, the Triennial—the organization’s first—was to be a multidisciplinary celebration of contemporary art from and about Asia. “We Do Not Dream Alone,” a truncated version comprising two exhibitions and a scattering of performance events, finally opened in October 2020, with a second part scheduled to run March 15–June 27.

In his curatorial statement, Tan asserts that the Triennial is designed to unveil the way people, objects, and events “are linked in a complex web of ties, associations, and relationships,” thereby attesting to “the power of art to resist our urge to silo during these uncertain times.” That this admirable sentiment is vulnerable to oversimplification is evident at the outset of the event’s titular exhibition at Asia Society. A pair of matching sculptures by Xu Zhen® guard the show’s entrance. Each comprises a headless copy of a traditional Cambodian sculpture grafted—vertically, neck to neck—onto a headless copy of a classical Roman figure, thus announcing the curatorial premise that in a globalized context all cultures are hybrid. Further amplifying this idea, the treacly strains of the Disney anthem “It’s a Small World” waft through the second-floor galleries. The soundtrack’s source is an installation by Ken and Julia Yonetani. Not surprisingly, the Yonetanis employ this tune ironically as part of a critique of the twentieth century’s misplaced confidence in the benefits of nuclear energy. But the song inevitably colors all the surrounding works, enfolding them in a soporific plea for cultural harmony.

Selections both reinforce and push back against this narrative. Natee Utarit’s painting The Dream of Siamese Monks (2020) provides a textbook illustration of hybridity. Based on a nineteenth-century Thai painting, it is a mishmash of images of colonial architecture, neoclassical sculpture, Western tourists, and a Buddhist monk pointing toward a giant lotus. More intriguing in its cross-cultural references is a special project by Xu Bing and Sun Xun, “We the People.” Guest-curated by Susan L. Beningson of the Brooklyn Museum, the installation suggests the interplay between Chinese and American political thinking. An official nineteenth-century print of the American Declaration of Independence anchors the project. Xu presents a silkworm-infested copy of The Analects of Confucius, an ancient text on familial duties and good government that influenced several Founding Fathers. Sun contributes a long scroll painting that mixes traditional Chinese characters and motifs with broken fragments of the Statue of Liberty. Handwritten denunciations of tyranny from the Declaration of Independence imply a damning judgment on the recent politics of China and the United States.

At times the exhibition stretches the geographic definition of Asia almost to the breaking point, thus undermining the promise of common cultural inheritance. The Syrian-born artist Kevork Mourad emphasizes regional differences in Seeing Through Babel (2019), a model of the fabled Tower of Babel constructed from hand-drawn architectural cutouts. Minouk Lim’s Running on Empty, on the other hand, presents three totemic sculptures surrounding a video assembled from a 1983 broadcast documenting efforts to reunite Korean families torn apart by the Korean War. The faces of hopeful, despairing, and—in a few cases—joyfully reunited family members speak to the particularities of Korean history without having to belabor the work’s relevance to the current issue of family separation at the US-Mexico border.

The second exhibition, “Dreaming Together,” at the New-York Historical Society, gives visitors a glimpse of what the originally envisioned civic extravaganza might have entailed. Culling works from the collections of Asia Society and the Historical Society (where she is curator of American art), Wendy N.E. Ikemoto has created interesting conversations across cultural and historical divides. The first of the show’s four thematic sections, Nature, includes such delights as a pair of meticulously realistic nineteenth-century still lifes by Martin Johnson Heade, set alongside Zhang Yirong’s exquisitely executed ink-on-silk Spring Peony III (2014). The People section pairs works like George Henry Boughton’s 1867 painting Pilgrims Going to Church and Stafford Mantle Northcote’s 1899 Hi Hee, Chinese Theatre, Pell St., New York City. While the former’s somber pilgrims reinforce the founding mythology of a white Protestant America, the latter’s depiction of a performance of Cantonese opera in Lower Manhattan suggests the nation’s more diverse reality. In City, visitors find such matchups as photographs by Zhang Dali showing the abrupt modernization of Beijing juxtaposed with shots of urban decay in Harlem by Marc Winnat. The Protest section includes poster images by Kalaya’an Mendoza and Kenn Lam advocating Asian/African American solidarity.

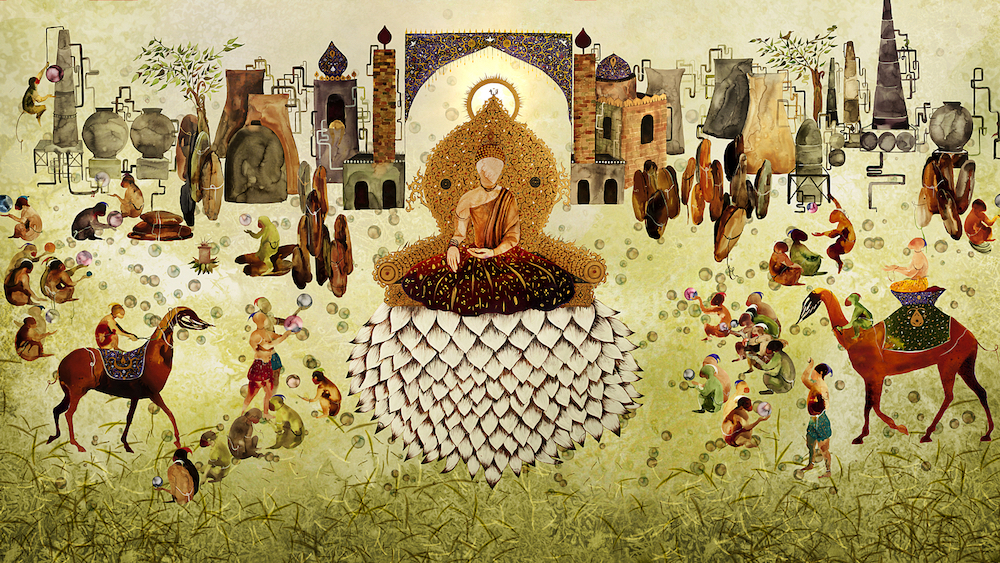

But overhanging all these mini-stories was a larger narrative suggested by the inclusion of the Historical Society’s celebrated painting cycle “Course of Empire” (1833–36) by Thomas Cole. These five tableaux chronicle the rise and fall of a great civilization. Placed at the outset of the exhibition, they set an elegiac tone that is picked up by references in various works to the destruction of the World Trade Towers, the demolitions wrought by gentrification, and the destruction of political monuments. Matching Cole in epic ambition was Lotus, a 2014 video animation by Shiva Ahmadi that depicts the transformation of a peaceful Buddhist kingdom into a dystopia of war and destruction.

The Asia Society Triennial suggests the evolution of pan-Asian exhibitions. After a hiatus during the market-driven years of the early twenty-first century, explorations of identity in art and art criticism are back in full force. But identity takes on a new complexion in a world shaken by financial crises, pandemic, right-wing nationalism, and, in the US, unapologetic racism. The 1990s discourse on the “Other” assumed a binary opposition between mainstream and margin, which served to implicitly elevate “non-Otherness” as the norm. By contrast, twenty-first-century identity emphasizes hybridity, intersectionality, and the leveling of hierarchies. But is this just another soothing myth?

While “We Do Not Dream Alone” conveys a hopeful message about multiculturalism, “Dreaming Together” suggests that our commonalities are less about shared cultural traditions than about a collective potential for universal annihilation. In that sense, a “small, small world” is a terrifying prospect.

This article appears under the title “Asia Society Triennial” in the March/April 2021 issue, pp. 63—64.