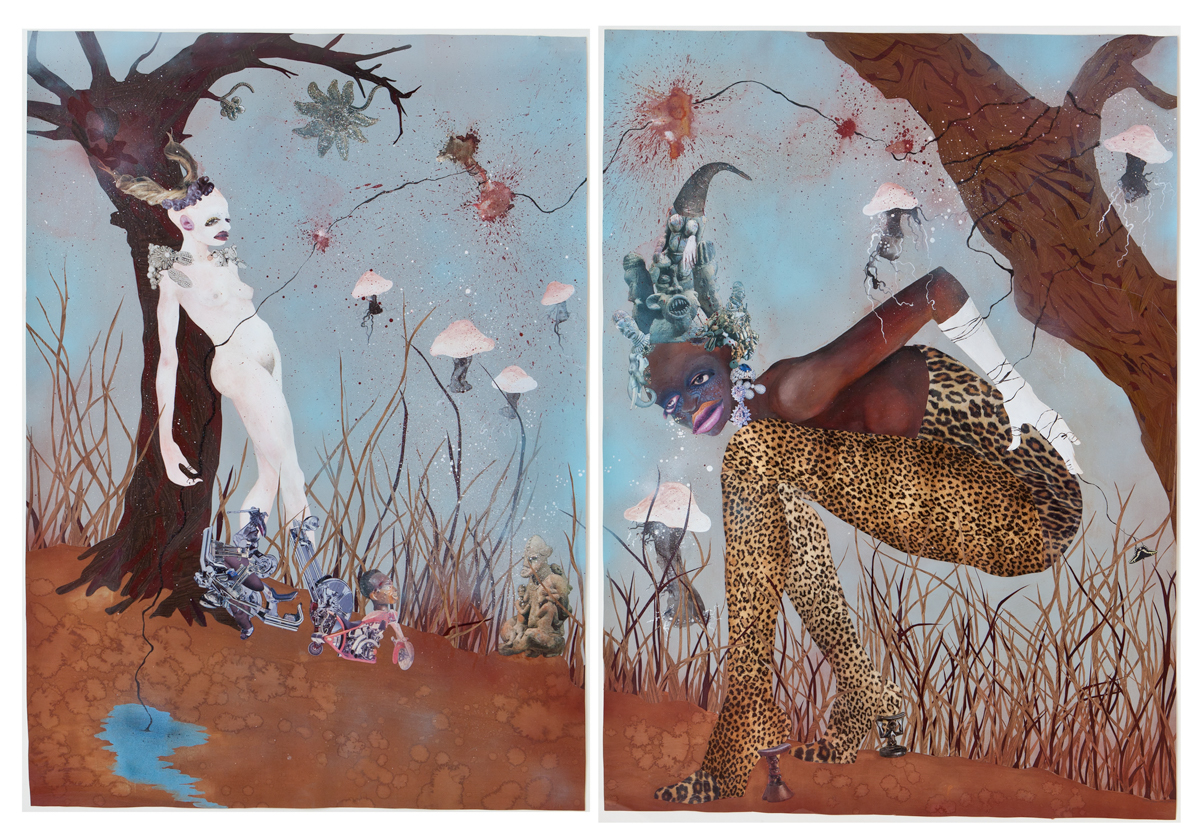

GODDESS FIGURES—many of them familiar from imagery from Luban, Yoruban, and Mangbetu traditions—appear throughout Wangechi Mutu’s current midcareer retrospective at the New Museum. There they keep company with a remarkable pantheon of hybrid creatures that blend animal, mineral, and vegetable characteristics to suggest a mystical female power rooted in nature and ancient mythologies. In her glowing review of the show, Roberta Smith refers to her “magical matriarchy” and suggests that the show reveals Mutu to be “one of the best artists of her generation.”

It wasn’t long ago that the mention of goddesses or matriarchy would have condemned an artist to the nether world of irrelevance. But now, Mutu emerges as one of the foremost practitioners of contemporary Goddess Art, and these become words of praise.

Though long stigmatized, the reputations of artists identified with the original Goddess movement of the 1960s—among them Mary Beth Edelson, Ana Mendieta, and Judy Chicago—have soared in recent years. The presiding spirit of last year’s Venice Biennale was Surrealist artist Leonora Carrington, who identified the “greatest revelation of my life” as Robert Graves’s book The White Goddess, a study of mythology and poetry in pre-Christian nature-based matriarchies. The British Museum recently offered a mammoth examination of female spiritual figures across cultures and historical periods. And younger artists like Saya Woolfalk, Chitra Ganesh, and Lina Iris Viktor seem increasingly comfortable with invocations of female deities and spiritual powers.

What accounts for this sea change? Significantly, this renewed interest in icons of female power comes at a moment when political and social institutions are actively threatening female autonomy at home and abroad. Then, there is the fact that the original movement embraced a gender-fluid concept of the Goddess that resonates today. Meanwhile, the climate crisis underscores the urgent need for a different understanding of nature, progress, and technology. The Goddess movement’s holistic theory of nature is compatible with current developments in the fields of biology and ecology. And new scholarship in anthropology and archaeology lends support to the idea that early societies were, if not strictly matriarchal, at least matrilineal and matrilocal. In the art world, all this adds up to a growing awareness that many of the artists originally associated with the Goddess movement were unfairly maligned. Now, a group of younger artists is finishing what they started.

THE GODDESS MOVEMENT was born in the early 1960s, when second-wave feminists bolstered their indictment of toxic patriarchy with alternative visions of society, history, and gender relations. Many were energized by archaeological discoveries that pointed to the prehistoric existence of ancient matriarchies and to widespread worship of female deities. These ideas coalesced into the Goddess movement, a celebration of feminine spirituality that served as inspiration to numerous artists, scholars, and writers.

Critic Gloria Feman Orenstein surveyed the work of these artists in an essay in the spring 1978 edition of Heresies, a self-described “Feminist Publication on Art and Politics” that ran between 1977 and 1993. Issue #5, The Great Goddess, comprises a collection of poems, artworks, scholarly essays, and speculative fantasies that reveal the range and complexity of women’s views on the subject. It includes lists of megalithic temples associated with goddess worship, prescriptions for the creation of new rituals, explorations of Indigenous spiritual practices, and celebrations of menstruation and childbirth. Some contributors search for empirical proof of prehistoric matriarchies, while others regard such societies as simply metaphors or useful guides to thinking about a post-patriarchal future.

Orenstein’s essay includes Carolee Schneemann, who evoked the Minoan Snake Goddess by placing two snakes on her body for her 1963 Eye Body performance; Ana Mendieta merging her body with the earth; Mary Beth Edelson channeling ancient goddesses in ritual performances; Betye Saar creating talismans to honor Black Goddesses and Voodoo Priestesses; Betsy Damon bypassing the patriarchy in performances that assumed the part of a 7,000-year-old woman; and Judy Chicago crafting a creation myth with a goddess as the supreme creatrix.

Running through the projects presented in Heresies is a sense of excitement over the possibilities unleashed by these feminist challenges to the male-centric Judeo-Christian theologies that have dominated Western culture. But the contributors are adamant that they are not seeking a simple reversal of power. As religion scholar Charlene Spretnak remarked in her anthology, The Politics of Women’s Spirituality (1982), “no one is interested in revering a ‘Yahweh in a skirt.’” Instead, the Goddess emerging from Heresies is less a person or an individual agent than a nexus of nature, spirit, and body. She represents social cooperation and attunement to the forces of nature. While male power emphasizes domination and control, the contributors argue, goddess-inspired female power yields a more cooperative society, one that recognizes the rights of other people, other species, and the earth itself.

Heresies wrote revisionist histories, identifying precedents for this concept in early human societies. They found support from scholars. In Lost Goddesses of Early Greece (1978),Spretnak revives an ecosystem of female deities that preceded the Greek Olympians. Artist and writer Merlin Stone’s 1978 When God Was a Woman documented the suppression of goddess societies in the Middle East by a triumphant Abrahamic culture. Cultural historian Riane Eisler’s The Chalice and The Blade: Our History, Our Future (1987) explored the tensions between two models of society—feminist partnership cultures versus patriarchal dominator cultures—that have persisted throughout human history.

A key figure in this rethinking of history was archaeologist Marija Gimbutas, a specialist in Neolithic and Bronze Age cultures. Her 1974 book The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe challenged standard accounts of European prehistory that suggested inequality was inevitable as societies scaled up, divided labor, and pivoted to agriculture from nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles. She posited the existence of cooperative, peaceful, female-centered social orders in the Neolithic era, and theorized that these were wiped out beginning in 4400 BCE by nomadic warring Bronze Age invaders. While other scholars had largely downplayed the significance of female figurines, dismissing them as mere fertility goddesses, she saw them as figures embodying the making and destroying of life whose powers were at the center of these societies’ female-oriented spiritual belief systems. She argued that the societies of Neolithic Europe were largely peaceful, “matristic” (a word describing their deference to female authority that she preferred to “matriarchal”), and attuned to nature and goddess worship.

Unlike subsequent patriarchal cultures that envisioned nature as an external entity and a resource to be dominated and exploited, these early societies, Gimbutas argues, worshiped the “unbroken unity of one deity, a Goddess who is ultimately Nature herself.” This concept of nature finds a striking parallel in the work of chemist James Lovelock and microbiologist Lynn Margulis who, in the early 1970s, developed the Gaia Theory. According to the Greek poet Hesiod, Gaia was the child of Chaos who brought the world into being and also produced such fearsome races as the Titans, Giants, and Cyclopes. As creator and destroyer, she was hailed as the Great Mother, the origin of life, and the personification of earth. Inspired perhaps by the Goddess vibes floating around in the 1970s, Lovelock and Margulis attached the name Gaia to their concept of the planet as a self-regulating system. They argued that living organisms evolve in response to their surroundings, both animate and inorganic, to maintain the conditions for the continuation of life. Gaianism paints a picture of the interdependence of life and nonlife that mirrors the beliefs of early Goddess societies.

Gimbutas’s work did not age well. While The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe became an important resource for artists and writers associated with the Goddess movement, Gimbutas’s academic fate suffered, in part due to her association with the Goddess artists. Once a towering figure, she was charged with the sins of essentialism and utopianism, and dismissed as a crank or fantasist. Academic rivals disseminated a caricatured version of her views, made light of her research and professional qualifications, and ignored the widespread respect her peers accorded her. Today, few archaeological texts cite her work.

In the 1980s, the Goddess movement took a hit. The idea of women building shrines to pagan goddesses, performing rituals to mark the phases of the moon, or conjuring the spirits of women burned as witches seemed anti-intellectual—and frankly, embarrassing. The Goddess fixation smacked of wishful thinking, of surrender to New Age fantasies of lost matriarchal utopias, and of a retrograde equation of women with nature. It seemed essentialist, ahistorical, and rife with cultural appropriation.

As the 1980s wore on, celebrations of matriarchy gave way to gender deconstruction. A feminist identification with Mother Earth was supplanted by Barbara Kruger’s cry, “We won’t play nature to your culture,” the title of her landmark 1983 show. Then, Donna Haraway declared in A Cyborg Manifesto (1985), “I’d rather be a cyborg than a goddess.”

IT TOOK A RETROSPECTIVE of feminist art—“WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution,” which opened in 2007 at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles—to remind the art world of the original Goddess movement artists. The same year, “Global Feminisms” at the Brooklyn Museum featured works made from 1990 onward, under the influence of a variety of transnational spiritual traditions. But there was still stigma. As art historian Jennie Klein noted in 2009, “the Goddess is the unacknowledged white elephant in the room of feminist body art.”

Alongside renewed interest in the original Goddess artists, new scholarship now supports Gimbutas’s account of Neolithic history. In The Dawn of Everything (2021), a monumental reconsideration of the origins of human society by anthropologist David Graeber and archaeologist David Wengrow, Gimbutas reemerges as a visionary. The authors contend that “among academics today, belief in primitive matriarchy is treated as a kind of intellectual offence, almost on a par with ‘scientific racism,’ and its exponents have been written out of history.” Yet they point to new evidence of the relatively peaceful and egalitarian societies that Gimbutas described, and confirm that these were indeed, as she suggested, largely destroyed from 4400 BCE on by marauding Indo-Europeans whose societies were prone to violence, indifferent to art and nature, and dominated by men. Graeber and Wengrow argue that Gimbutas’s dismissal can be understood in part because she “was attempting to do something which, until then, only men had been allowed to do: craft a grand narrative for the origins of Eurasian civilization.”

Meanwhile, Haraway, once a goddess denier, has more recently embraced Lovelock and Margulis’s concept to describe the interdependence of organic, inorganic, and mechanical forces—including, famously, the cyborg. Today, the Gaianism movement holds an important, though controversial, place in discussions about biology, chemistry, genetics, and environmentalism. Proponents stress cooperation and revere mutualistic relations, emblematized by the holobiont—a unit made up of one host, plus the other species that live in, on, or around it. This idea encourages a kind of ecosystemic thinking—an awareness of and reverence for the other species surrounding us—that has had tremendous impact

on artists today.

Margulis, who in 1991 coined the term holobiont and placed symbiosis—mutually beneficial relationships—at the center of cellular evolution, was the presiding spirit over a recent exhibition at the MIT List Visual Arts Center. Titled “Symbionts: Contemporary Artists and the Biosphere,” the show focused on artists who explore instances of Gaianist mutualism. While these artists might not characterize themselves as goddess worshipers, their work expresses a vision of nature very close to Gimbutas’s “unbroken unity” of the Goddess. The artists probe various forms of symbiotic entanglement by introducing spiders into the gallery (Pierre Huyghe), interrogating the intelligence of bacteria (Jenna Sutela), transforming soil into currency (Claire Pentecost), and “painting” with freshwater algae (Anicka Yi).

MORE TRADITIONAL GODDESS IMAGERY is found in the British Museum’s recent exhibition “Feminine Power: the Divine to the Demonic.” But here too, it is clear that goddesses are not simply the obverse of a singular male creator god. Rather, female deities and demons play many roles in the creation and destruction of life. At one extreme is the rebellion against authoritarian male power embodied in Kiki Smith’s 1994 sculpture Lilith,which presents Adam’s disobedient first wife as a glowering she-demon crouching on the wall. Lilith exists on a continuum that also embraces the creative forces of nature, the maternal instincts of protection and nurture, and the reason-defying seductions of sexuality. At the opposite end of the spectrum from Lilith’s vengeful glare is a sense of solidarity and mutualism that reflects the entangled relationships between all life-forms celebrated by the “Symbiont” artists.

“Feminine Power” brings together secular and sacred artifacts from six continents dating from 6000 BCE to the present. Curator Belinda Crerar divides her selections into categories that stress creation, compassion, and desire, as well as disruption and force. She mingles contemporary works by artists like Kiki Smith, Alison Saar, Mona Saudi, Judy Chicago, and Wangechi Mutu with Cycladic fertility figures, Yoruban water goddesses, Tantric scrolls, Mesopotamian amulets, and Buddhist statues of Guanyin. Two striking themes emerge from this wealth of material: the transnational nature of goddess imagery and the widespread evidence throughout history of a gender-fluid concept of divine power. In many cultures, the earth divinity or creator deity displays masculine and feminine characteristics.

In its Great Goddess issue, Heresies sought a cross-cultural approach, with essays on Native American spiritual practices, West African secret female societies, and Indian Goddess worship. Nevertheless, like second-wave feminism generally, the Goddess artists of the 1970s presented a largely white demographic. Gimbutas’s focus on Old Europe may have contributed to the Eurocentric orientation of many of the artists for whom she was a guiding light.

Contemporary Goddess artists—Mutu chief among them—share their predecessors’ desire to use icons of female power and divinity as a springboard to envision new futures. But the new and more diverse generation brings a wider range of cultural references to the table. Mutu contributed an unsettling female figure composed of soil and ornamented with charcoal, oyster shells, feathers, hide, porcelain, and hair to “Feminine Power.” In the catalogue, she describes the work, Grow the Tea, then Break the Cups (2021), as a guardian figure endowed with a feminine intelligence. The artist elaborates: “I feel that in general women think about the future, different species, more than men. Women’s intellect, instincts and intuition are essential if we want to continue living in this world.” The Kenya-born artist’s current retrospective offers perspectives on East African creation stories and Caribbean mythology.

Not content with the essentialist conflation of women with life-giving forces of goddess art past, artists like Morehshin Allahyari and Chitra Ganesh don’t shy away from the less savory implications of gender-fluid divinity. Not all their goddesses play nice. Ganesh’s monumental 2015 Eyes of Time installation at the Brooklyn Museum paid homage to Kali, Hindu goddess of destruction and rebirth. Tri-breasted and multiarmed, Ganesh’s Kali has a clock in lieu of a head. The clock signifies that we have now entered a period called Kali Yuga, the final tumultuous age in the Hindu cosmic cycle in which the destruction of our world will herald the beginning of a new Golden Age.

New York–based Iranian artist Allahyari has been engaged in a multiyear project similarly dark in tone, using 3D printing to revive a coterie of fearsome jinns—shape-shifting spirits from Islamic literature and pre-Islamic legend that Allahyari reimagines as nonbinary, proto-feminist figures. One of her recurring characters is the jinn Huma, traditionally depicted as a demon with three heads and two tails. In pre-Islamic and Islamic mythology, Huma is responsible for human fevers; in Allahyari’s formulation, the spirit presides over the planet’s fever in the form of global warming. As the artist told an interviewer for Hyperallergic, “I’m not interested in the motherly goddesses. I’m only interested in the dark ones and the monstrous ones, and the cruelty of each of their powers that will take over something.”

For this new generation of feminist artists, Goddess imagery offers a language for exploring concerns like environmentalism, indigeneity, and gender fluidity. While they share the original Goddess artists’ worship of the feminized values of care and cooperation, the new generation also reflects our era’s anxiety and apocalypticism. In place of uplift, they are conscious of the potential for civilizational collapse. Climate change suggests that the nature goddess can take as well as give. While the original Goddess artists emphasized the nurturing side of female deities, it must be remembered that goddesses like Ishtar and Kali were both makers and destroyers of life. Adopting the language of Gaianism, Mutu suggests what is at stake today, remarking: “Building on the backs of other human beings by ravaging, squandering and pillaging depletes the earth and us all. The planet is intelligent and alive and constantly reminding us what it can be like, if we treat each other fairly.”