What good can art do? As the world appears to spiral out of control, a rising tide of authoritarianism swells here and abroad. Acts of astonishing bravery in places like Ukraine and Iran are met with crushing violence, while implacable forces drive an ever-widening wedge between those who wield power and those who are subjected to it.

Art seems a poor tool to address these problems, and yet artists continue to make the attempt. Why, and to what effect? These are the questions that shape Kaelen Wilson-Goldie’s new book, Beautiful, Gruesome, and True. Published by Columbia Global Reports, an imprint of Columbia University, it is not exactly a conventional art book, as it contains no pictures, and not exactly a piece of investigative reporting, as it presents no conclusions or solutions. Instead, it offers three carefully researched case studies of artists whose work has sprung from some of the most intractable conflicts currently underway throughout the world. In place of illustrations, Wilson-Goldie offers descriptions of works and referrals to websites where they can be seen. For the reader, the result is somewhat unsatisfying but may be a harbinger of a future where images are a luxury only mass-market books can afford.

Typically, artists working in a political mode challenge social, economic, or civic institutions—including the institution of the art world itself—in the name of social justice. In these cases, they can still appeal to a widely shared sense of order, a set of principles, however tarnished. Wilson-Goldie has chosen to write about artists working in places where governmental institutions have collapsed or capitulated to outside forces, allowing criminality and violence to flourish. In such circumstances, Wilson-Goldie argues, art may operate as a proxy for political discourse that has otherwise been suppressed.

Wilson-Goldie, a Beirut- and New York–based art writer, weaves together biographical narrative, information about the sociopolitical context of artists’ works, and descriptions of specific projects. She writes in an engaging style, but her oddly shifting time frames can make the stories somewhat hard to follow. Each of her case studies involves artists moved to act by horrific events in their native countries. While all have subsequently garnered international art world accolades, acclaim seems beside the point. The work is driven by anguish, rage, and a desire to reach out to others who have also been affected by the evils pervading their world.

Amar Kanwar’s films and installations are created against the backdrop of India’s land battles. His galvanizing moment was the 1991 assassination of Shankar Guha Niyogi, a charismatic trade unionist whose efforts had brought together steel workers, Indigenous farmers, and contract miners in a formidable challenge to prevailing top-down models of rural and industrial development. With his death and the ultimate failure of authorities to bring his assassins to justice, his movement faltered. (The industrialists accused of ordering his murder were initially found guilty, only to have their convictions overturned by a higher court.)

Kanwar was a young filmmaker whom Niyogi had hired to document his activities; but instead of meeting his new employer, the artist arrived in time for his subject’s funeral. He remained to film the aftermath. Lal Hara Lehrake(1992), his short film documenting the outpouring of grief and anger over the murder, set him on a path to explore other collusions between government officials and masters of industry. He has examined such topics as the destruction of farmland and natural resources, land grabs by multinational companies, and the rise of resistance movements. While his immediate targets are specific acts of corporate greed and government corruption, his larger concerns encompass the social and political inequities and environmental devastation visited on rural communities by the global economy.

Kanwar eschews the role of muckraking documentarian, instead searching for a language that melds poetry with resistance. His films take a variety of forms. A Night of Prophecy (2002) carries us across India as individuals recite bits of poetry decrying both economic and caste-based discrimination. A Season Outside(1997) combines memories, dreams, archival footage, and reenactments to explore the scars of Partition, the 1947 division of the Indian subcontinent into Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan.

An important early supporter was the late curator Okwui Enwezor, who commissioned A Night of Prophecy for his legendary Documenta 11 in 2002. Kanwar was included in the next three consecutive Documentas as well. His most ambitious project for that event was “Sovereign Forest,” a multimedia work for Documenta 13 in 2012. Its subject is the political and environmental conflict in the resource-rich and largely tribal Indian state of Odisha. The installation’s many parts include handmade books with films projected on their pages; maps; news clippings; samples of the huge varieties of native rice that have disappeared with the onset of industrial farming; and a 2011 film titled The Scene of Crime, which documents landscapes selected for impending industrial development. The work has evolved into an ongoing project that travels the world, as viewers contribute further evidence of the degradation of tribal lands.

WILSON-GOLDIE’S SECOND CASE STUDY is Teresa Margolles, whose work has evolved in the context of Mexico’s drug wars. These conflicts have empowered vicious cartels, engendered widespread military and police corruption, and turned the border between Mexico and the United States into a killing field. Again, globalism has been a contributing factor in this downward slide: The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between the US, Canada, and Mexico, signed in 1994 as part of an effort to facilitate free trade among the three countries, inadvertently facilitated the illegal drug trade as trucks more easily crossed from Mexico into the US. In the process, it has decimated local economies in cities like Tijuana, Juarez, and Matamoros. In such border towns, the cartels have emerged as a kind of alternative government.

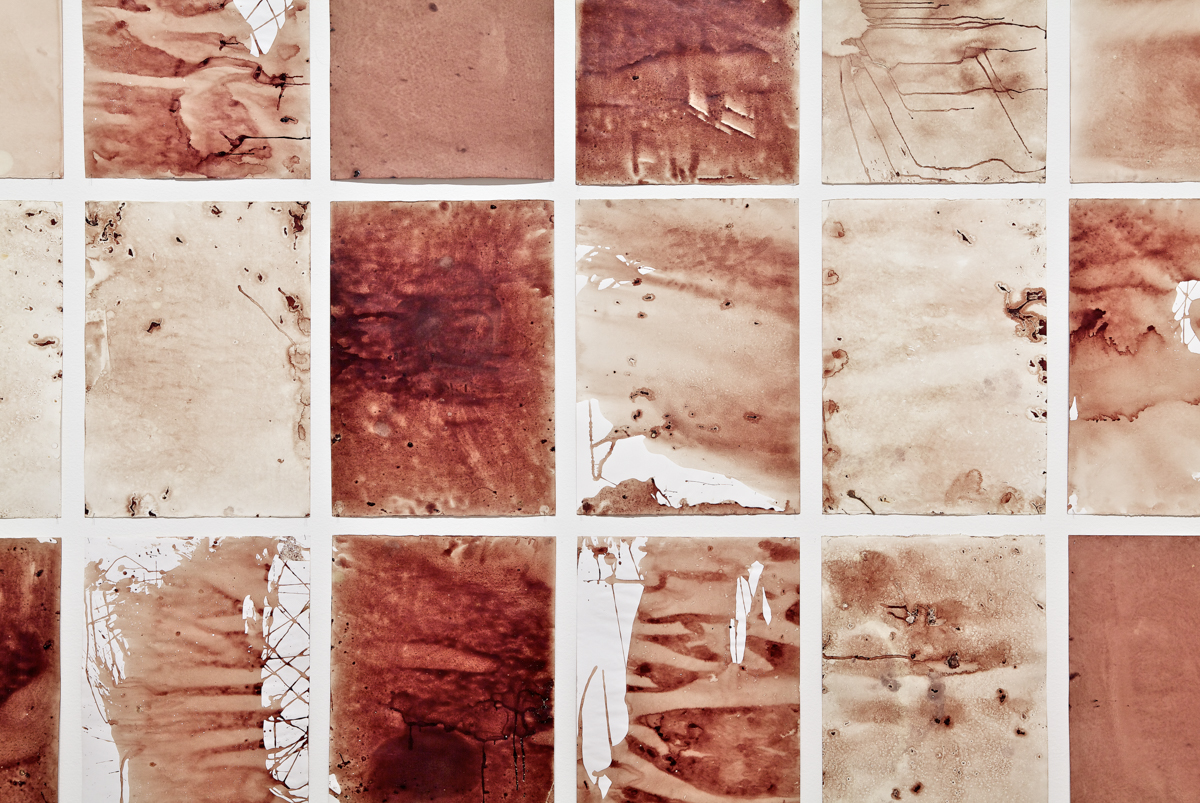

Margolles’s work makes the violence precipitated by this social breakdown visible to the world at large. Her materials comprise forensic evidence. She uses fabric soaked with the water used to wash corpses, mud from sites where cartel victims are buried, shards of glass from windshields shattered in drive-by shootings, and blood mopped up from crime scenes. While the materials are gruesome, the works themselves tend to be understated. A minimalist or conceptual aesthetic serves as a foil, making it all the more shocking to learn that a red flag is dyed with blood from execution sites or that a Richard Tuttle–like arrangement of strings comprises threads used after autopsies to sew up the bodies of persons who suffered violent deaths. Wilson-Goldie focuses in particular on Margolles’s contribution to the Mexican Pavilion for the 2009 Venice Biennale, where visitors were led through a series of galleries that distributed her unsettling works throughout the decaying 16th-century palazzo.

Margolles came to this work with a background in documentary photography and forensic pathology; but probably more relevant was her participation in SEMEFO, a Mexico City–based art collective that specialized in disturbing works employing such elements as animal cadavers and human remains. After the group’s dissolution in 1999, Margolles continued in a similar vein, while directing her work toward more explicit connections between violence and the global drug economy.

As Wilson-Goldie points out, there is a strong collaborative element in Margolles’s work. She collects her necro-based materials from families of victims and includes them in ritual actions and performances. Most recently, Margolles has been focusing on transgender sex workers, who are among the few denizens left behind in certain neighborhoods of Juarez in the wake of murders, violent crime, and the closing of the dance halls where they worked.

THE THIRD CASE STUDY BRINGS US Abounaddara, a Syrian film collective whose mostly anonymous members posted brief weekly videos on the internet between 2011 and 2017, during the worst years of the Syrian civil war. Wilson-Goldie begins her story in the early 2000s, when the death of Syria’s right-wing dictator Hafez al-Assad led to hopes of a more open and democratic society. However, after some initial reforms, these hopes were dashed when his son and successor, Bashar al-Assad, proved equally repressive. Abounaddara emerged when a group of independent filmmakers came together to create short online videos. These were designed to evade official censorship by appearing to be simply trailers for films yet to be made.

Wilson-Goldie focuses extensively on Maya Khoury, one of the group’s founders and one of the few members to emerge from anonymity. A self-taught filmmaker like many in the collective, Khoury was initially motivated by the desire to complete a project about an elderly clothmaker working in the Old City of Damascus. Her frustration with the distribution options available to her led to the formation of Abounaddara.

Pro-democracy uprisings roiled the Arab world in 2010 and 2011, leading to the short-lived hope for an “Arab Spring.” Following the crushing of these hopes, Syrians responded to brutal suppression with weekly Friday protests. This became the time frame for the release of Abounaddara’s films. These short clips, which remain available online, are deliberately fragmentary. They employ a variety of formats, including pop references, surrealistic juxtapositions, reportage, literary allusions, and brief interviews. While not explicitly political, all are tinged with the frustrations, dangers, and absurdities of the everyday life of ordinary Syrians making the best of an impossible situation.

Work produced by Abounaddara is less easily assimilated to art world institutions than that of Wilson-Goldie’s other case studies. This is in part because of the decentralized nature of the group, and probably also because their films are directed primarily at local rather than international audiences. As a spokesperson for the group explains: “Our priority is not to criticize the regime. We address our people with our images to prove to them that their experiences and their dignity matter.” Thus, though Abounaddara began to receive invitations to prestigious exhibitions like Documenta and the Venice Biennale in the second half of the 2010s, the collective ultimately resisted this notice. Its weekly films ceased in 2017. Plans for longer films petered out, with a feature film commissioned for the 2017 Documenta left unfinished, never making it past a rough cut.

In place of a conclusion, Wilson-Goldie gives us an epilogue in which she reports on the unraveling of Abounaddara, Kanwar’s participation in the selection of the Indonesian collective ruangrupa as the organizers of the recently closed (and very problematically received) Documenta 15, and Margolles’s commission to create a temporary public monument to transpeople in London’s Trafalgar Square. It seems telling that these stories end not with a report on their impact on their respective causes but with the varieties of art world attention they have received. As a result, despite these artists’ inspiring examples, one is left with a sense of the distance between the art world’s self-congratulatory embrace of such heroic activities and the gritty and seemingly intractable problems they address.

What good can art do? The case studies here leave one with the sense that art in the political arena operates as a means of bearing witness, fostering empathy, and engendering relationships among the victims of global power plays. In her preface, Wilson-Goldie remarks that while this work implicates everyone, it may have its biggest impact on the art world and its debates over who brokers power. That seems laudable, but is it enough? In the face of the horrific threats to individual and collective human survival documented here, one can’t help but wish for more.