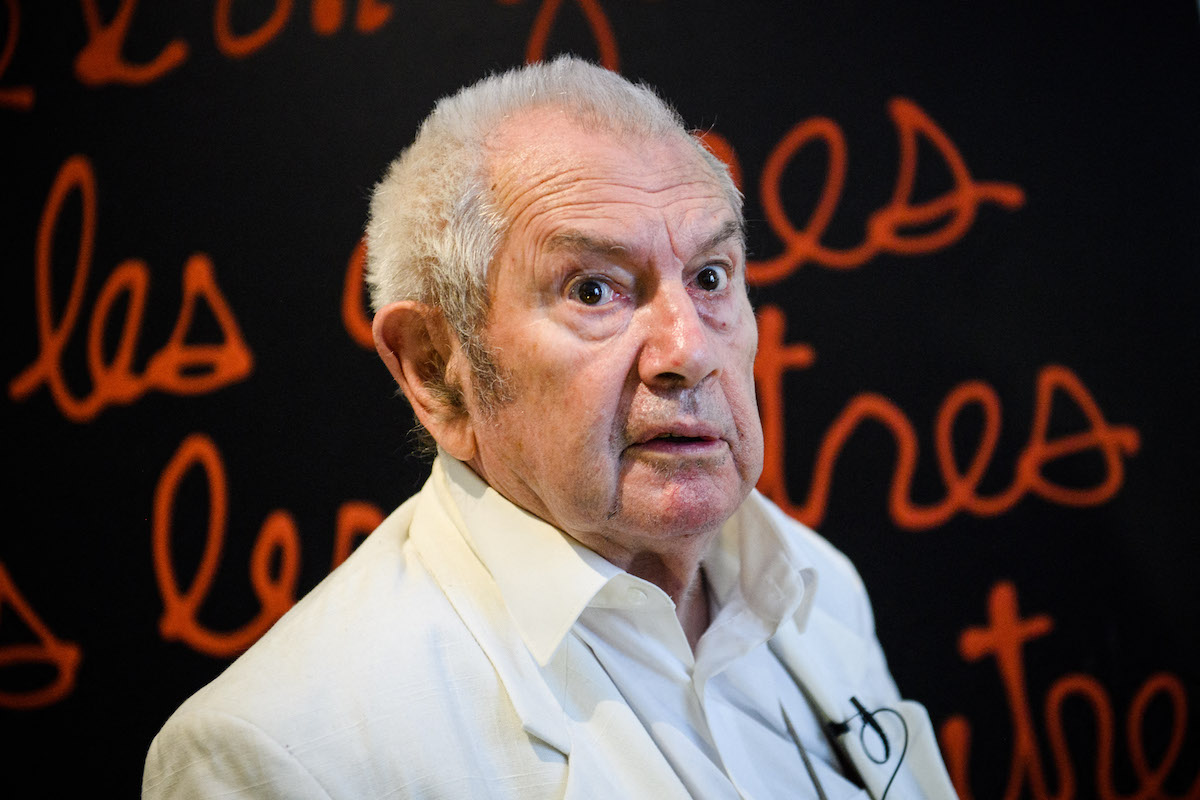

Ben Vautier, a French Fluxus artist whose humorous paintings and performances imploded the division between life and art, earning laughs and admiration alike from critics, has died at 88.

Vautier, who often worked under the artistic moniker Ben, was found dead in his home in Nice on Wednesday, less than a day after his wife died following a stroke. The Nice prosecutor’s office said that his body was discovered with a gunshot wound; the office said it would open an investigation to determine the cause.

Ben, along with other artists associated with the Fluxus movement of the 1960s, set out to blur all boundaries between the everyday and the hallowed field of art-making. He succeeded in doing so, creating artworks that sometimes incorporated the detritus of life itself, helping to point art in a new direction in an era when high-minded abstract painting was still preferred by the establishment.

He is remembered for one aphorism in particular: “Everything is art,” a phrase that he wrote in paint over and over, with many different variations, during the course of his six-decade career. Yet he was fond of creating paradoxes as well, and would sometimes intentionally contradict himself in other artworks and writings.

“Art is not LIFE but life communicated by X,” he wrote in 1966. “My EVERYTHING is for me an EVERYTHING of sincerity and of contradiction. It wants to be a BOUNDLESS EVERYTHING CONTAINING ALL the other’s EVERYTHING. That is, therefore, a work of pretension.”

At the 1972 edition of Documenta, the famed art festival in Kassel, Germany, Ben put it more bluntly, hanging a gigantic banner over the Fridericianum museum that read “KUNST IST ÜBERFLÜSSIG,” or “Art is superfluous.”

Among his most famous creations is Le magasin de Ben (1958–73), an installation that started out as a functional shop in Nice. What began as a store for buying records and cameras soon became something more than that: a “total art center,” in Ben’s terminology, whose walls were scrawled with the artist’s cursive phrases and hung with overflowing wheels, hats, and knickknacks.

Although the installation is now considered an important artwork, Ben last year told Forbes that it was “not for the art crowd because the art school was 100 meters away and the students were forbidden from coming to my place.” Today, it resides with Paris’s Centre Pompidou, which is currently showing the piece within its galleries.

Benjamin Vautier was born in 1935 in Naples, Italy. After his parents divorced when he was a kid, he led an itinerant childhood, moving with his mother from Egypt to Switzerland before finally putting down roots with her in Nice. He did not do well in school in that coastal French city, so his mother got him work in a local bookstore, where he aided in English translations. His first significant experience with art, he said, was not in a museum or a gallery, but in that shop, where he would excise portions of books he liked and collage them together at home.

“Then I developed a theory when I was 18 or 19: art must be new,” Ben said in the Forbes interview. “So I came to art like that.” He never attended art school.

His shop in Nice became known to members of the French avant-garde, including Yves Klein and Martial Raysse, who exposed him to the concurrent Nouveau Réalisme movement. Ben recalled showing Klein his drawings of bananas, which Ben took as his subject because he believed no other artist had ever done so. Klein, unimpressed with the bananas, said he was more interested in Ben taking up the written word and linking up with the Lettrists, who had enlisted text in visual forms. But Ben found Lettrist art to merely be “mannered graphics,” and instead sought a more truthful form of text.

Ben’s official introduction to the Fluxus movement came in 1962 through its founder, George Maciunas. Drawing on the Dada movement from a half century prior, Maciunas’s Fluxus manifesto, written the following year, called on artists to “PURGE the world of dead art, imitation, artificial art, abstract art, illusionistic art, mathematical art.” That spirit was already in the air, and Ben thrilled to it, heeding Maciunas’s advice to seek out works by John Cage and George Brecht.

In 1963, Ben organized a Fluxus festival in Nice, bringing over artists like Nam June Paik and Benjamin Patterson to perform there live. Ben would continue creating similar events with his own concept of total theatre, which was designed to bring performances off the stage, into life itself. A pesky prankishness pervaded Ben’s total theatre: he once convinced a theater that he was going to stage a production of a Molière play, then proceeded to smash pianos and fill a room with paper.

Though Ben’s paintings and related ephemera remain his most famous works, he also gained renown during the 1960s and ’70s for his performance art, which was deliberately crass. One piece consisted of urinating in a jar, then exhibiting the vessel as an artwork; another involved Ben repeatedly ramming his head against a wall. Anyone could’ve done these quotidian actions, but Ben performed them as art, so onlookers were forced to accept them as such.

Critics did not always respond kindly to Ben’s provocations, especially the ones produced during the ’80s and onward. “Tout est art? Maybe, but not all of it belongs on display,” quipped Quinn Latimer in Frieze in 2010, writing on the occasion of a massive Ben retrospective staged at the Musée d’Art Contemporain in Lyon, France.

Others were more charmed by Ben’s humor. In 1998, the New York Times devoted an entire review to Ben’s photography, addressing works such as Polaroids that were entirely blank. “‘I am not a good photographer,’ he confidently announced. That’s fair. No one will ever confuse Ben with Ansel Adams,” critic Vicki Goldberg wrote. “But whether in English or French, he poses more philosophical questions about the medium than Adams had time for, in a dry and even ridiculously naive manner, as if he were explaining Roland Barthes on ‘Sesame Street.'”

Whatever criticisms followed Ben throughout his career, they seemed to fade away on Wednesday as French officials mourned him. Rachida Dati, France’s culture minister, called him a “legend,” writing in a post on social media, “We will miss his free spirit terribly, but his art will continue to make France shine throughout the world.”

Ben may have been accused periodically of egotism—allegations that were no doubt aided by the fact that he created a persona called Mister EGO. But he generally approached his art in a plainspoken way that befitted his project of reaching the general public.

He once told curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, “My definition of art is: astound, scandalize, provoke or be yourself, be new, create.”