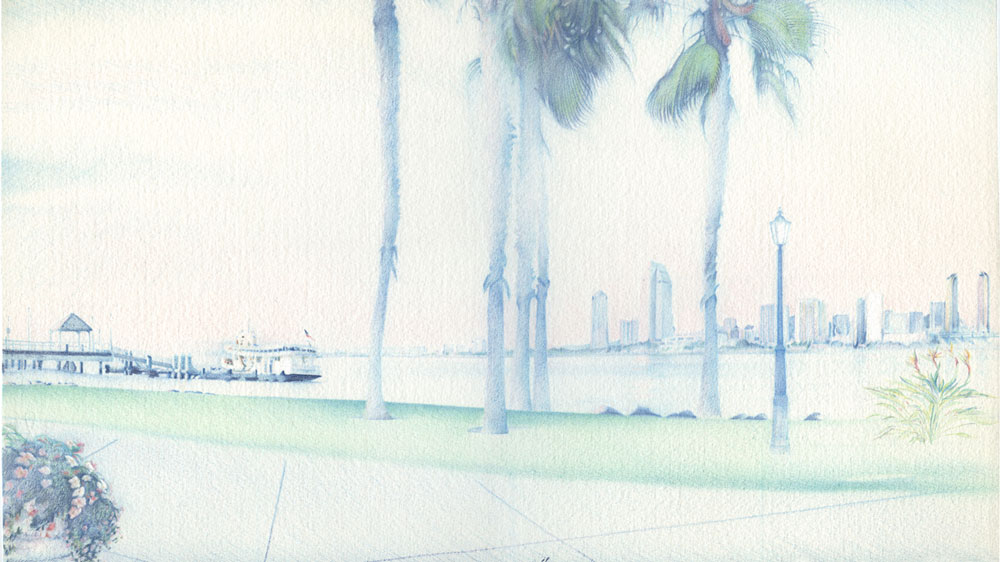

Dino Aranda’s landscapes are untroubled, even idyllic. The watercolorist depicts his vistas in a dreamy haze, their edges soft but vibrant colors. White-gray light saturates the setting, as though diffused through cloud cover.

Compare them to the work Aranda created fifty years ago, and one would think they’re looking at the work of an entirely different artist. Aranda’s work in the 1960s and 1970s was set in desolate grays and earth tones, defined by visceral linework and rugged impasto. Color gradually began to creep back into Aranda’s art in the 1980s, after the Sandinistas overthrew the Somoza family dictatorship, which, for decades, ruled his native Nicaragua with an iron fist. It is as though Aranda has not only found paradise but is painting it.

Born in Managua in 1945, Aranda showed an early aptitude for art. Between 1957 and 1963, he attended Managua’s School of Fine Arts, where he was mentored by Rodrigo Peñalba, widely considered the father of plastic arts in Nicaragua. Aranda absorbed his mentor’s modernist sensibilities while honing his own distinctive style of still-life painting.

After graduating, Aranda founded the Praxis Gallery Group along with fellow artists Alejandro Aróstequi, César Izquierdo, Genaro Lugo, Leoncio Sáenz, Orlando Sobalvarro, Luis Urbina, and Leonel Vanegas. The artists were bound together by a resistance to the abstractionist and social realist strains dominating Latin American art at the time.

In 1965, Aranda moved to Washington, D.C., receiving a Ford Scholarship to study at the Corcoran School of Art. Despite leaving Nicaragua, his art continued to confront the brutality of the Somoza regime, the family dictatorship that ruled Nicaragua from 1936 to 1979. During this time, The Washington Post praised his “delicate abstraction” and described a 1992 retrospective of his work at the Fondo del Sol Multicultural Museum as “genius… a powerful show of brooding, semi-abstract images that speak to the human trauma and terror of a nation consumed by revolution for several decades.”

In the 1980s and 1990s, Aranda continued to incorporate the Indigenous Mesoamerican symbols that had surfaced his earlier work—particularly those of the Maya, his own heritage. He was especially drawn to Quetzalcoatl as a symbol of rebirth and spiritual syncretism, completing three series of paintings on the feathered serpent god between the 1970s and 1990s.

In 1999, Aranda left Washington, D.C., for Southern California. “I was ready for a new direction,” he told ARTnews. In recent decades, his work has moved away from political engagement and towards lush, soft-focus landscapes inspired by his time in California, Arizona, and Florida. Aranda’s work remains in the permanent collections of D.C.-area museums like the National Gallery of Art, the National Museum of American Art, and the Art Museum of the Americas.

He is now based in Sedona, Arizona, where he lives with his wife, an immigration lawyer serving asylum seekers and families separated at the U.S.-Mexico border and sells his work at dinoarandaartist.com.