Georgia O’Keeffe and Henry Moore, the great naturalists of modernism, both died in 1986, an ocean apart.

They were apart nearly every moment of their lives, too. The Wisconsin-born O’Keeffe graduated from art school and moved to New York, where a career whirlwind awaited; Moore, a Brit and eleven years her junior, had his studies interrupted by a draft into the first World War. O’Keeffe eventually left the city for the desert; Moore made his studio in the dewy English countryside.

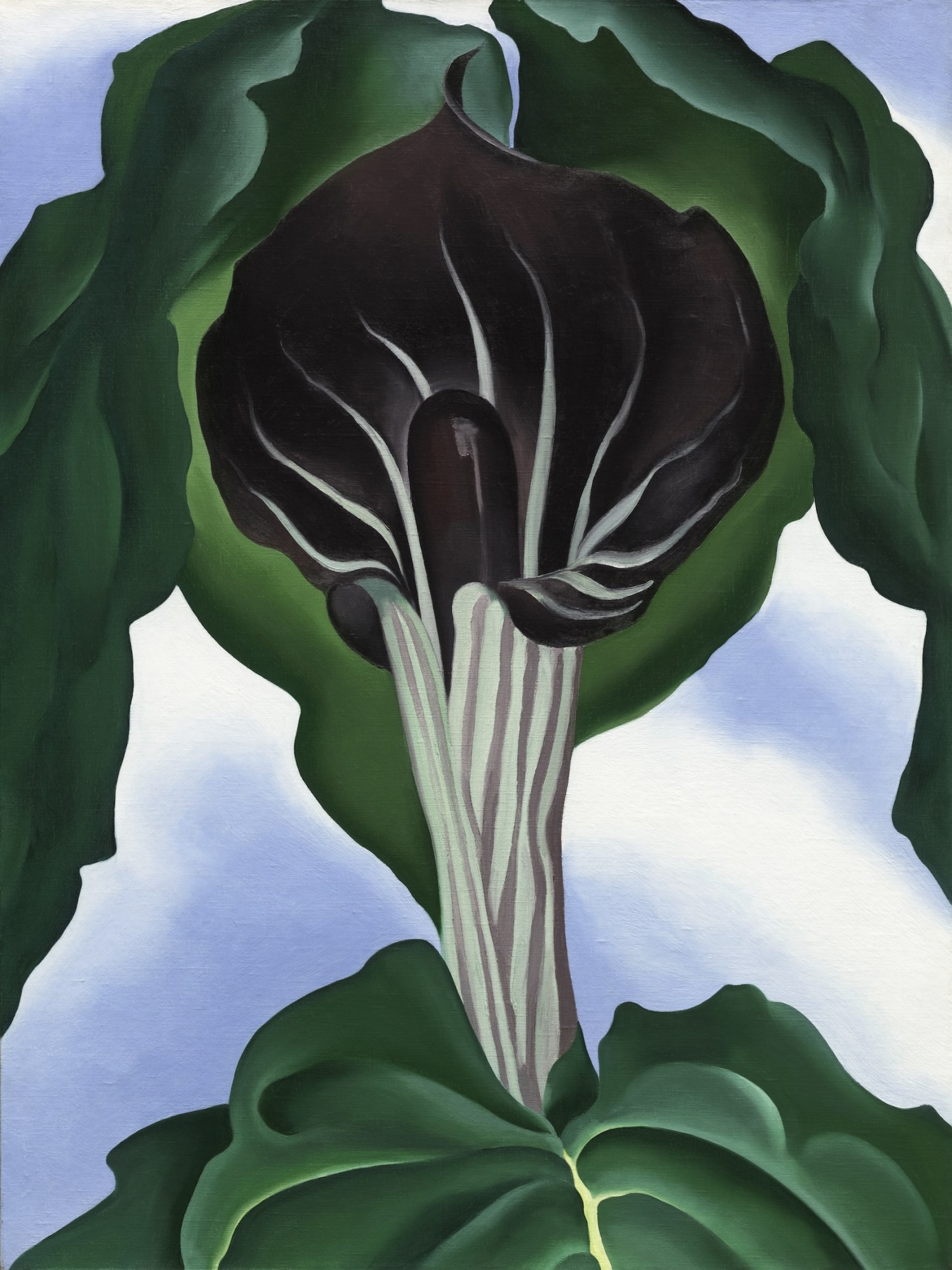

The artists approached abstraction from different dimensions and geometries. Painting, O’Keeffe flattened and magnified the crags, petals, and bones of the American Southwest, pursuing the edge of recognition. Sculpting, Moore transmuted people and places into empty-chested objects woven with string, variably round and flat-edged; his stone breathes, just unlike us. Even their sole meeting is near apocrypha, given its a secondhand account. (Some say they shared words at an exhibition opening in New York.)

The talented curators at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) are among those “some”, and they say even more: that art history has done itself a disservice by studying O’Keeffe and Moore in isolation, as their parallels—their ambitions and obsessions—close the distance by every relevant measure. Those curators, headed by Iris Amizlev, make a convincing case in a landmark two-hander currently on view at the MMFA until June 2.

Titled “O’Keeffe and Moore: Giants of Modern Art”, it includes a wealth of drawings, paintings, and sculptures borrowed from the San Diego Museum of Art, the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, and the Henry Moore Foundation. There is photography, like a stunning portrait of O’Keeffe taken in her Santa Fe home, and a recreation of their final studios, meticulous to the historically accurate paint palettes and curiosity collection of animal skulls, pebbles, seashells, and artifacts. The exhibition is curated by Anita Feldman, deputy director for curatorial affairs and education at San Diego and Iris Amizlev, the MMFA’s curator of community engagement and projects. The epic subtitle, Amizlev explained, is for Moore, who’s not as well known in Canada.

Any comparative exhibition—and there’ve been a few lately—carries extra curatorial demands. Neither co-star should outshine the other and each artwork must argue for the show’s existence beyond putting two buzzy names on the same bill, especially when the artists barely shared air. No one wants two serviceable surveys stitched together; give us revelations visible only via proximity.

Throughout the sprawling display, the paired artists are newly contextualized by their material fascinations (scavengers and hoarders, both), associations with contemporaneous art movements (surrealism, mostly), relationship with femininity (fraught and frustrated), and national identity, among more. The curators in particular revel in unraveling the critical mis-takes that have dogged both since their debuts.

One of the best pairings is among the first that visitors will encounter, two small sculptures of the female form, O’Keeffe’s Abstraction (1916) and Moore’s Composition (1931). Moore purportedly had mommy issues, while O’Keeffe labored to escape a sound bite from her husband, Alfred Stieglitz (“At last, a woman on paper!”) Her papers, populated with blown-up blooming flowers, still get mistaken for sexual innuendo.

Moore sculpted and sketched over his lifetime voluptuous women reclining, Olympia-light, or working at industrious pursuits like winding wool and tending children; around 1930, he sculpted about a dozen iterations of the last scenario, including Composition. Now what was the truth? He hailed from a big, happy family, and once remarked that he “could see the mother” in everything— “I suppose I’ve got a mother complex” — and said that his first sculptural experience was smoothing oil onto his mother’s back. This is the sort of sticky sentiment no journalist could ignore.

He explained himself better too late, calling the motif an extension of his rejection of European art tradition and its fuss about perfection; “a universal theme from the beginning of time and some of the earliest sculptures we’ve found from the Neolithic Age are of a mother and child,” he said. Moore, after all, practiced what he called “truth to materials”, meaning material shouldn’t imitate flesh; wood is wood, stone is stone.

That Freudian hullabaloo fades away in the presence of O’Keeffe’s sculpture of her dead mother, interpreted here as a white-robed apparition, faceless, bent at the waist, and wasted away.

In this show, neither artist comes off as particularly autobiographical. Odd anthropologists, they memorialized remembered emotion, like how love and sorrow contort the body. They did so with some differences, as O’Keeffe was more obviously curious about the world as she singularly experienced it.

Take the two artists’ studies of “tunnels”: Moore is represented in a series of quick sketches of people sheltering underground during the Blitz, the bombing of London in World War II. Faced with a terrifying fate (but very boring present), the silhouettes can only huddle in place, doze, or hold one another. He had a sculptural way of drawing, layering figures in pencil, then white wax crayon, and finally colored crayon, to create a three-dimensional effect. These are effectively juxtaposed with O’Keeffe’s painting of spiraling wood grain, devoid of people, pure perspective.

The show takes pains to differentiate between abstraction and surrealism, which have a sort of frog and toad dynamic. The former is a choice of interpretation; the latter is a way of life. O’Keeffe and Moore were tangential to the movement—Moore even served on the selection committee for the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London and showed seven works in it—but neither ascribed to its ideology. And how could they? Surrealists surface from dreams with incoherent souvenirs.

O’Keeffe and Moore were ascetics in comparison. To them, everything interesting already exists and can be whittled to its essence. O’Keeffe’s bones and horizons always get their due, but I remembered best her interpretations of seashells, which both artists collected according to some enigmatic criteria. Maybe their greatest strengths, illustrated here powerfully, was an unerring notice of nature’s parallels, like how the inner coils of a shell resemble entrenched canyon rivers. The shell’s aperture opens shyly on the canvas, if only you could peer inside like O’Keeffe, holding a pelvis bone to her eye, and catch the vision within.

“It is surprising to me to see how many people separate the objective from the abstract,” O’Keeffe said, “Objective painting is not good painting unless it is good in the abstract sense…” This was around 1930, after the sensational New York debut of her charcoal drawings, and just as the Earth had clarified itself as a smattering of line and color.

She added: “Abstraction is often the most definite form for the intangible thing in myself that I can only clarify in paint.”