Scattered around downtown Baltimore are benches emblazoned with the phrase “Baltimore: The Greatest City in America.” By contrast, the novelist Richard Price once proclaimed the city to be “Chaos Theory incarnate.” In conversation with its inhabitants, you are likely to hear words like “lopsided” and “idiosyncratic.” But Baltimore boasts a tight-knit arts scene that is thriving. “There’s a true support system here,” said Amy Eva Raehse, director of the gallery Goya Contemporary. “In other cities people seem to be competing for success. The art community in Baltimore seems to be moving forward together.” This coming fall, the director and artist John Waters, the bard of Baltimore, will have a career retrospective at the Baltimore Museum of Art titled “John Waters: Indecent Exposure.” ARTnews paid a visit to him as well as other artists and spaces that put the charm in Charm City.

ALL IMAGES: ©KATHERINE MCMAHON

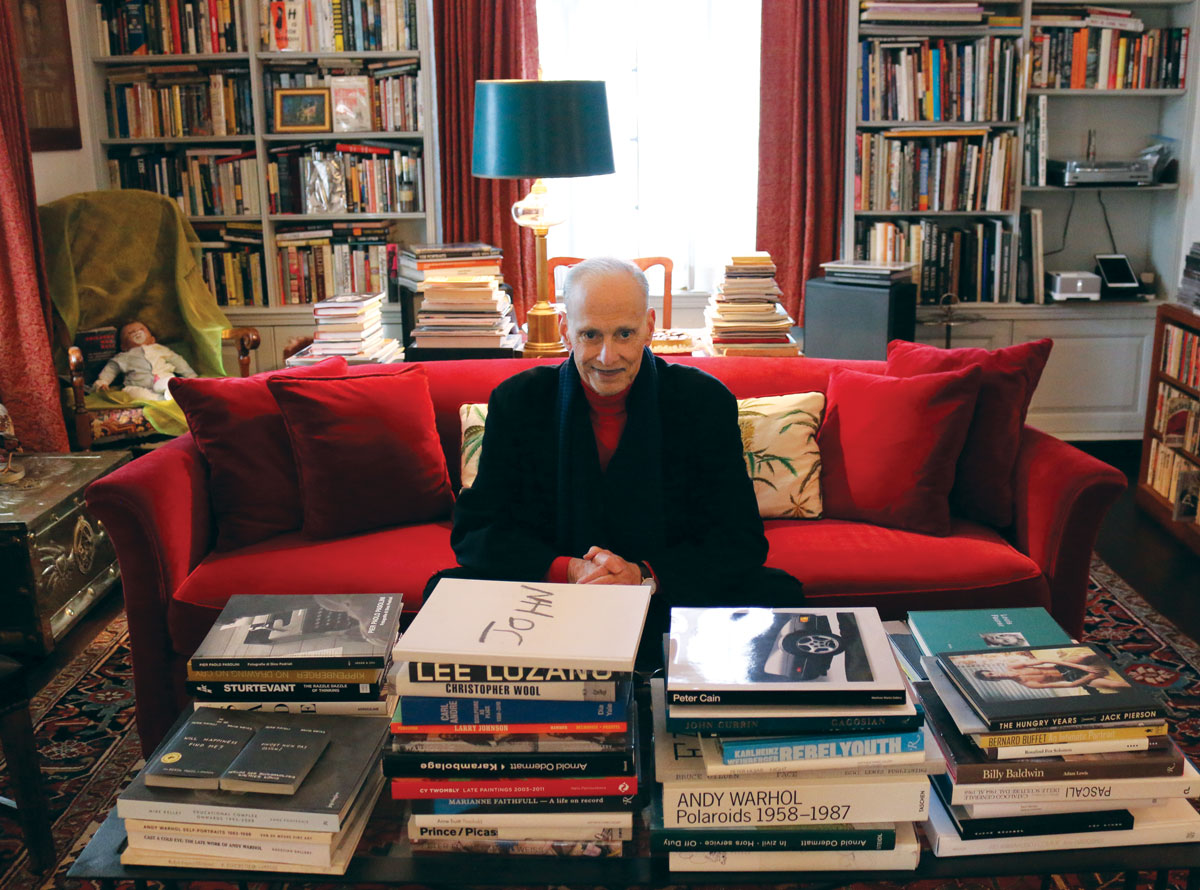

John Waters

“It’s as if every eccentric in the South decided to move north, ran out of gas, and decided to stay,” John Waters said of his hometown. Born in Baltimore and closely associated with it ever since, Waters had his first experiences of art at the Baltimore Museum of Art, the very museum that will soon host his retrospective. “The first thing I ever bought with my own money was a Miró print at the BMA gift shop when I was ten years old,” he said. “I hung it up and all the kids were like ‘Ewww, that’s ugly!’ I saw the power of art and how it infuriated people. I was immediately drawn.” About his city, he added, “I don’t think Baltimore has an inferiority complex anymore, but it’s still cheap enough to have a bohemia and it has the best sense of humor about itself of any town.”

The sculptor, printmaker, performance artist, and jewelry designer Joyce J. Scott has lived in her West Baltimore home for more than 40 years. “I’m a neighborhood ‘around the way girl,’ but I aspired to global knowledge.” Though she has traveled extensively, she feels a sense of responsibility to her home city. “Any postindustrial city is having trials about race, economics, and class,” she said. “If art is part of social justice, we artists will keep doing what we’re doing. It’s not only good for the artist but for the entire community.” Scott, who was awarded a MacArthur “genius grant” in 2016, is currently the subject of a solo exhibition at Grounds for Sculpture in Hamilton, New Jersey. She will have her first solo show in New York in 20 years at Peter Blum Gallery in September.

The conceptually inclined musical duo Matmos—Drew Daniel and M. C. Schmidt—have lived in Baltimore since moving from San Francisco nine years ago. A stark difference they noticed was in cost of living. “It’s a city where you can’t ignore the differences and distortions that wealth produces,” Daniel said. “The structure that makes it affordable is part of a longer story about other people’s poverty—you’re enmeshed with that. It’s always in this weird state of life-death.” In a basement studio at their row house in Charles Village, Matmos is currently working on a new album using only sounds generated with plastic, including a police shield they found on eBay.

“This building is a mystical spot,” said Twig Harper, who purchased the 5,000-square-foot West Baltimore edifice that would come to be known as the eclectic live/work space Tarantula Hill. “If you can make something happen in a void where everything’s been sucked out, it’s more vital than having institutional support.” Harper—who also makes noise music and rents time in his in-house sensory-deprivation tank—shares the space with the textile artist April Camlin, photographer Lindsay Bottos, and performance artist Michael Wasteneys Stephens. About the Baltimore art scene, Camlin said, “It’s harder to find a commercial gallery here—most of the galleries are artist-run. It’s not as conducive to making money off your practice, but there are a lot of opportunities.”

In the wake of Nudashank, a dynamic and catalyzing gallery they ran together for four years, Alex Ebstein and Seth Adelsberger recently debuted their new Resort gallery on the ground floor of a three-story building in the Bromo Arts District. “There are a lot of large spaces and a lot of people here for the academic art community who stay and make ambitious work because they have the space to do so,” Ebstein said. In addition to their duties at the gallery—whose next exhibition, a group show titled “Noise Margins,” opens in late March—Ebstein and Adelsberger are both also practicing artists. “Even though we’re not at the center of the market,” Ebstein said, “it continues to be inspiring to live and work here.”

Painter Carolyn Case has been a big part of the Baltimore art scene as it has grown in the two decades since she moved for grad school and ultimately came to teach at the Maryland Institute College of Art, one of the oldest art schools in the country. “A lot of funding for the arts has been an excellent development,” she said, “as have grants for small independent galleries, which have helped stabilize them.” She also credited free-admission policies at the Baltimore Museum and the Walters Art Museum for creating accessibility, and spoke of inspiration she finds for paintings of her own in an aging urban landscape. “This city has lots of painted-over textures: thin coats over corrugated metal, delicate layers over structures that feel weighty.”