The threads of history, the sinews that tie us to our ancestors, course through the work of María Magdalena Campos-Pons. They take the form of roots, threads, and umbilical cords throughout her survey at the Brooklyn Museum. In the show as in her life, history is ever present. The artist was born in Cuba in 1959—the year that saw Fidel Castro sworn in as prime minister—and she spent part of her childhood in the same barracks that had housed her great-grandfather, Gabriel, a Yoruba man who had been kidnapped from West Africa in 1867 and forcibly enslaved in the Caribbean. The artist left Cuba in 1990, living in Canada for a year before taking up residence in the United States, where she started working as an artist. Because US-Cuba relations hardened after she arrived, it took 11 years before Campos-Pons was finally able to return to Cuba.

Throughout the ’90s, Campos-Pons worked on an installation-based trilogy titled “History of a People Who Were Not Heroes,” and the second entry in this series, Spoken Softly with Mama (1998)—a work she made in collaboration with composer and jazz musician Neil Leonard—opens the show. Against a black wall rest four blown-up archival photographs of Campos-Pons’s family, and three video screens that show various dreamlike shots of the artist; these seven upright elements are, in fact, ironing boards. Carefully arranged on the floor before them are dozens of glass irons and mirrors. The work pays homage to Campos-Pons’s women ancestors who have sustained the family by doing domestic work. “Their caretaking seems to have helped guide her on a path toward social justice,” art historian Selene Wendt writes in the exhibition catalogue.

But Spoken Softly with Mama is also undergirded by a more sinister history: the legacy of chattel slavery, which ebbs and flows through much of Campos-Pons’s work. Slavery made Black women’s role as domestic laborers distinct from other women’s—they were often forced to work in the homes of others, not just for their own families. A critical gaze gives the ironing boards the contour of slave ships that would have brought kidnapped Africans across the Atlantic to the Americas.

A 1994 photograph from the series “When I Am Not Here / Estoy Allá,”one of the artist’s first works using large-format Polaroids, similarly considers the impact of slavery on Black motherhood. In this image, we see Campos-Pons’s torso painted blue, adorned with curving white lines that mimic waves. The blue nods to Yemayá, the orisha of the sea and motherhood in Santería. Two baby bottles that drip breast milk hang from her neck, connected by a tube. (At the time, Campos-Pons had recently given birth to her son Arcadio.) Cradled in her hands is a carved wooden ship. The photo cuts off her head and legs; this mother’s body has been fragmented by forced migration, severed from her roots.

Forced migration recurs in TRA (1991), for which Campos-Pons pairs 60 black-and-white portraits of generations of Afro-Cubans from Matanzas, once the heart of Cuba’s sugar plantation economy, with five boards shaped like boats. This time, upright wooden planks are painted to resemble the infamous diagram of a slave ship, numerous Black bodies shown cramped together in the hull. The work is powerful to behold.

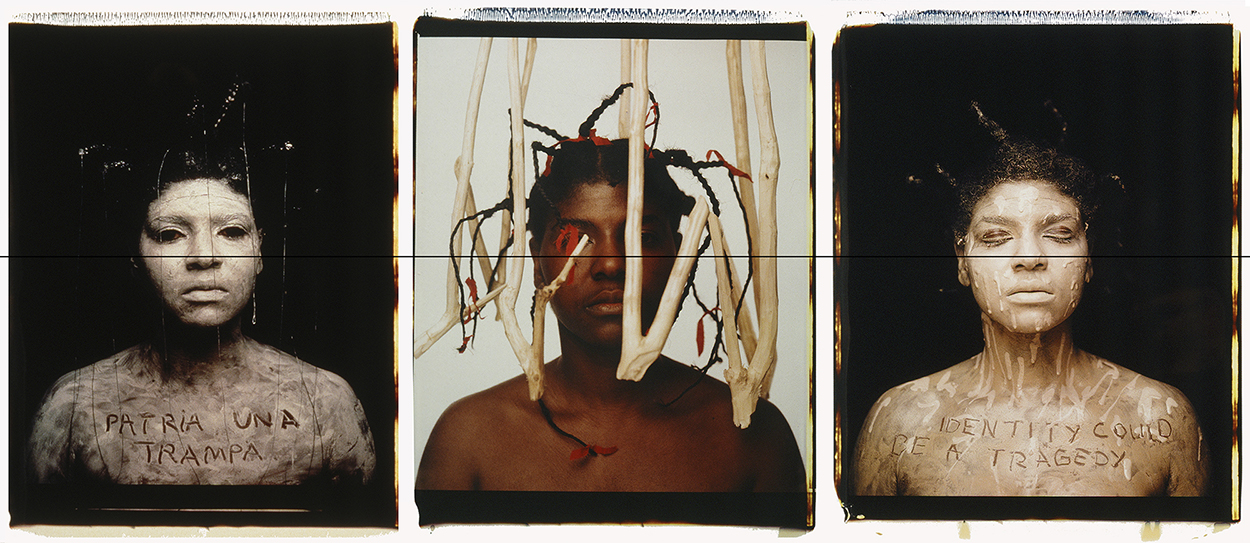

The Brooklyn Museum exhibition, which will travel to three venues across the country, leans heavily on Campos-Pons’s use of multipart, 20-by-24 Polaroids. Her technical prowess in staging these scenes—mini-performances in themselves—is in full effect in works like Finding Balance (2015). In 28 Polaroids that together comprise one scene, Campos-Pons stands before the camera, her face painted white. A birdcage rests atop her head, and she wears an antique Chinese robe, a nod to her Chinese ancestors who were brought to Cuba as indentured servants to work on the sugar plantations.

Another Polaroid knockout is the nine-part grid Classic Creole (2003). In the center, a yellow flower rises from a tall fabric-wrapped form that close inspection reveals to be a human body. On either side, strings of beads rise up like trees in a clever play with scale. The work evokes cultural, bodily, and natural roots all at once. “I am from many places,” Campos-Pons has said. “I live with that duality and multiplicity in my mind, and in my soul, and in my body. My roots are a bunch of dispersed fragments in the planet, in the universe, in this incredible miasma that is the world.”

Those metaphorical and literal roots run throughout the exhibition. Replenishing (2001) is a work that references retracing her lineage: it depicts the artist and her mother when they were finally able to reunite in Cuba. In the h-shape composition (for hogar, or home), her mother appears at left in a blue floral dress, the artist, at right in a white dress. The dresses represent the colors of orishas Oshun and Yemayá. Both women hold strings of beads that knot together and meet in the central Polaroid.

Umbilical Cord (1991) similarly traces the artist’s matrilineal side. In a linear grid, we see 12 black-and-white photos, 6 of them torsos with white crosses painted on them, alternating with 6 photos of arms with the left hand outstretched; a thread projecting from each work connects them all. These images show the women in the artist’s family. In Cuba, it is through the left hand, called “the hand of the heart,” that bloodlines are extended from woman to woman. In her work, Campos-Pons makes monumental the various histories and cultures that flow through her family’s veins.

The legacy of slavery came to feel even more present to the artist after she moved South in 2018 to Nashville, relocating from Boston, per the wall text. In Tennessee, she became fascinated by the magnolia trees that grow all around the city. As she walks about Nashville, she photographs them; by now, she’s accumulated hundreds of images of these trees. She digitally printed one of those images on a mixed-media triptych, Secrets of the Magnolia Tree (2021), framing a self-portrait. As cocurator Carmen Hermo writes in the catalogue, “What have these trees themselves seen, their lives extending far longer than ours? Irrigated by the actions and inactions of humans as much as the water cycle, these trees hold memories, too.” Campos-Pons is still attending to the trees, hoping to learn more of the histories they hold. In all her work, time collapses as history and the present intertwine. Soon, the trees’ stories will reveal themselves to her.

Correction, October 11, 2023: An earlier version of this review identified Neil Leonard as Campos-Pons’s husband; he is her former husband.